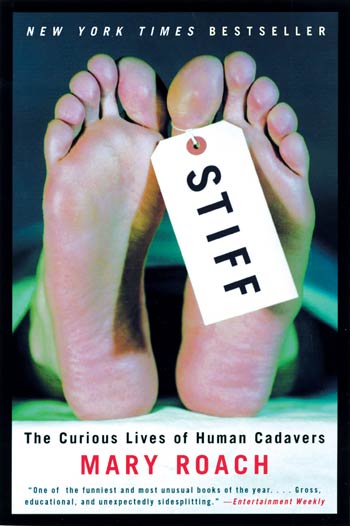

There are a lot of ways to tell if you're dead; heart not beating, the bright white light and seeing family members who have passed on. Or if there was absolutely no laughing while reading Mary Roach’s Stiff. That’s one sure-fire way to tell. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers uncovers the stories of the recently deceased and their fascinatingly gruesome history in a light-hearted way. But it is not for the faint of heart. The first line should prepare the reader for the rest of the journey: “The human head is of the same approximate size and weight as a roaster chicken.” Okay then.

There are a lot of ways to tell if you're dead; heart not beating, the bright white light and seeing family members who have passed on. Or if there was absolutely no laughing while reading Mary Roach’s Stiff. That’s one sure-fire way to tell. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers uncovers the stories of the recently deceased and their fascinatingly gruesome history in a light-hearted way. But it is not for the faint of heart. The first line should prepare the reader for the rest of the journey: “The human head is of the same approximate size and weight as a roaster chicken.” Okay then. The disgusting education continues from heads onto anatomy labs, the army, car crash tests and into the sticky subject of not-quite-dead cadavers. Each page has new tidbits and history, and with each fresh word the reader is learning without quite realizing it. And there is so much to learn. For instance, there are at least nine uses for a dead human that I bet no one has ever thought of before. Not only did Roach think of them, she investigated, illuminated and (dare I say) dissected each one.

The tone throughout this dissection is respectfully humorous, appropriately mirroring the attitude of the living who work with the dead. Roach handles the dead, and their keepers, with great care, making sure to never once cast a black shadow over this typically dark subject.

Reading Stiff is like traveling in a sidecar on Roach's journey; the reader experiences everything as she does, but once in a while she leans over to whisper something funny, slightly inappropriate and exactly what you were thinking. This book is written for the reader; unique photographs, footnotes at the foot of the page where they belong (unlike other books), and stories steeped in history.

The experience is more like a conversation with a friend than the one way dialogue of a novel. There is only one way this book will be read: voraciously.

Excerpt from Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers

Something else is going on. Squirming grains of rice are crowded into the man's belly button. It's a rice grain mosh pit. But rice grains do not move. These cannot be grains of rice. They are not. They are young flies. Entomologists have a name for young flies, but it is an ugly name, an insult. Let's not use the word "maggot." Let's use a pretty word. Let's use "hacienda."

Arpad explains that the flies lay their eggs on the body's points of entry: the eyes, the mouth, open wounds, genitalia. Unlike older, larger haciendas, the little ones can't eat through skin. I make the mistake of asking Arpad what the little haciendas are after.